MAIN GALLERY

Roots & Routes

The DC Arts Center’s

Sparkplug Artists’ Collective Presents

Curated by Gia Harewood

Featuring: Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal

APRIL 26 - MAY 26, 2024

MAIN GALLERY

The DC Arts Center’s

Sparkplug Artists’ Collective Presents

Roots & Routes

Curated By Gia Harewood

Featuring: Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot,

Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal

APRIL 26 - MAY 26, 2024

Roots & Routes is the culminating exhibition for the 2021 - 2023 cohort of The DC Art Center’s Sparkplug Artists’ Collective. These ten artists riff on the various meanings of roots as family, identity, and groundedness, along with routes as paths and journeys to raise the critical questions that invite introspection and even advocacy. In a sociopolitical climate that feels like it is stifling connection, collaboration, and calm, it is easy to lose hope.

However, Bryan Stevenson, lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, reminds us that hope is vital. He connects hope to the political and the personal, seeing it as inextricably linked to a just society. In his commencement speech to Ohio State University’s 2023 graduates, he says, “Our hope is key. Our hope is our superpower…hopelessness is the enemy of justice.” In many ways, this exhibition is ultimately about hope. To develop the superpower that Stevenson describes, the steadfast hope needed to weather any turbulent political or personal storms, we need to be grounded and firmly rooted; we each need to understand the histories of who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going to gather strength from these knowings—essentially the roots and routes of both self and society.

The exhibition first honors the roots of The DC Arts Center (DCAC) itself. Because its mission is to foster underrepresented artists, Sparkplug is a signature initiative that amplifies the organization’s roots. DCAC was founded as a platform for those who have been gatekept out of more traditional gallery spaces, thereby enabling a more diverse pool of artists (and curators) to reach wider audiences. At the same time, this exhibition also celebrates the various artistic routes that these creatives have traveled throughout the program and will continue to take in the future.

The ten featured artists—Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal—explore the exhibition’s theme according to what is most relevant and resonant to them and their practice. They not only provide many rich ways to think about roots and routes, they also remind us that to bring hope to our future we need to be firmly grounded and purposefully visioned—rooted and routed. However, hope is more than just optimism. The folks from the Equinox Counseling & Wellness Center in Colorado explain:

Hope is a sense that things can be made better through action, while optimism is a more ephemeral belief that everything will be OK…. Optimism is a positive thought pattern. Hope involves setting goals and following through on them. …hope is a more potent force and better for our health and well-being…. [because] Hope makes people act.

Knowing our roots and routes can help us take principled action. If nothing else, it can certainly be the catalyst for healing conversations in our personal and professional lives. The work gathered here helps to focus our attention on key considerations to make brighter tomorrows in our communities and beyond.

— Gia Harewood

Featured Above

Rebecca Perez

Our Lady of la casa, 2023

Carbon transfer, acrylic, colored laser paper, wood, string

24 x 39 inches

Featured Below

Gayle Friedman

Tempest, 2023

Repurposed bandsaw blades, steel wire, copper wire

67” L x 18” W x 18” H

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

ABOUT THE EXHIBITION

Roots & Routes is the culminating exhibition for the 2021 - 2023 cohort of The DC Art Center’s Sparkplug Artists’ Collective. These ten artists riff on the various meanings of roots as family, identity, and groundedness, along with routes as paths and journeys to raise the critical questions that invite introspection and even advocacy. In a sociopolitical climate that feels like it is stifling connection, collaboration, and calm, it is easy to lose hope.

However, Bryan Stevenson, lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, reminds us that hope is vital. He connects hope to the political and the personal, seeing it as inextricably linked to a just society. In his commencement speech to Ohio State University’s 2023 graduates, he says, “Our hope is key. Our hope is our superpower…hopelessness is the enemy of justice.” In many ways, this exhibition is ultimately about hope. To develop the superpower that Stevenson describes, the steadfast hope needed to weather any turbulent political or personal storms, we need to be grounded and firmly rooted; we each need to understand the histories of who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going to gather strength from these knowings—essentially the roots and routes of both self and society.

The exhibition first honors the roots of The DC Arts Center (DCAC) itself. Because its mission is to foster underrepresented artists, Sparkplug is a signature initiative that amplifies the organization’s roots. DCAC was founded as a platform for those who have been gatekept out of more traditional gallery spaces, thereby enabling a more diverse pool of artists (and curators) to reach wider audiences. At the same time, this exhibition also celebrates the various artistic routes that these creatives have traveled throughout the program and will continue to take in the future.

The ten featured artists—Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal—explore the exhibition’s theme according to what is most relevant and resonant to them and their practice. They not only provide many rich ways to think about roots and routes, they also remind us that to bring hope to our future we need to be firmly grounded and purposefully visioned—rooted and routed. However, hope is more than just optimism. The folks from the Equinox Counseling & Wellness Center in Colorado explain:

Hope is a sense that things can be made better through action, while optimism is a more ephemeral belief that everything will be OK…. Optimism is a positive thought pattern. Hope involves setting goals and following through on them. …hope is a more potent force and better for our health and well-being…. [because] Hope makes people act.

Knowing our roots and routes can help us take principled action. If nothing else, it can certainly be the catalyst for healing conversations in our personal and professional lives. The work gathered here helps to focus our attention on key considerations to make brighter tomorrows in our communities and beyond.

— Gia Harewood

Featured Above

Rebecca Perez

Our Lady of la casa, 2023

Carbon transfer, acrylic, colored laser paper, wood, string

24 x 39 inches

Featured Below

Gayle Friedman

Tempest, 2023

Repurposed bandsaw blades,

steel wire, copper wire

67” L x 18” W x 18” H

Opening Celebration

Friday, April 26, 2024

7:00 PM - 9:00 PM

Artist Talk

Sunday, May 19, 2024

3:00 PM - 4:00 PM

Closing Reception

Sunday, May 26, 2024

6:00 PM

EVENTS

EVENTS

Opening Celebration

Friday, April 26, 2024

7:00 PM - 9:00 PM

Artist Talk

Sunday, May 19, 2024

3:00 PM - 4:00 PM

Closing Reception

Sunday, May 26, 2024

6:00 PM - 7:00 PM

The beginning of a new calendar year tends to be filled with celebration and reflection, hopeful resolutions, and deep introspection. January itself often feels packed with a recharged promise of renewal, new chances to potentially do things differently, and overall commitments to be better. Yet, just four months into 2024, there are still multiple wars with increasing death tolls, continued climate destruction, punitive policies targeting marginalized identities, and intensifying political divisions. As the presidential election creeps closer and closer in the United States, sociopolitical hostilities feel like they are stifling connection, collaboration, and calm. It is easy to look at the news and lose hope.

However, Bryan Stevenson, lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, reminds us that hope is vital. In his commencement speech to Ohio State University’s 2023 graduates, he says, “Our hope is key. Our hope is our superpower…hopelessness is the enemy of justice.” Stevenson connects hope to the political and the personal; he sees a just society as inextricably linked to it. In many ways, I am also calling for hope. To develop the superpower that Stevenson describes, the steadfast hope needed to weather any turbulent political or personal storms, I believe we need to be grounded and firmly rooted; we each need to understand the histories of who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going so as to gather strength from these knowings — essentially the roots and routes of both self and society.

Because The DC Arts Center’s (DCAC) mission is to foster underrepresented artists, Sparkplug as a signature initiative amplifies the organization’s roots. DCAC was founded as a platform for those who have been gatekept out of more traditional gallery spaces, thereby enabling a more diverse pool of artists (and curators) to reach wider audiences. Having been a 2014 Curatorial Initiative awardee, I am grateful for how their presence jumpstarted my curatorial career, and I am honored to be back in this full-circle then-and-now moment.

This exhibition also celebrates the various artistic routes that these creatives have traveled throughout the program and will continue to take in the future. However, as Toni Morrison states in her 1987 novel Beloved, “Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.” To that end, these ten artists—Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal—explore the exhibition’s theme in unique ways, sharing what is most relevant to them and resonant with their practice. I am energized by their visions of what art can do and am hopeful that their talents will inspire audiences to find common ground and face the difficult dialogues and decisions in our sociopolitical futures.

Several artists use found objects to plumb the depths of family histories. Gayle Friedman has a reverence for things that people no longer find useful and bandsaw blades give her the perfect material manifestation for how we walk in the world. She describes it as a combination of “tension and danger.” However, I was even more fascinated with how the blades provide a powerful metaphor and entry point into racial dialogues. She is a white Jewish woman from an all-white suburb just outside of Birmingham, Alabama who was unaware of the racialized violence happening just a few miles away until she moved out for college. Therefore, I see the tension and danger in the toll that racism takes on everyone—sometimes it is exposed and raw (like the unpainted blades), sometimes it is covered up and packaged (like the painted blades), but either way, it can never be contained—it will always break through the surface (like the blade jutting over the panel board’s frame).

Rebecca Perez also digs into her family’s Puerto Rican roots through material objects. Having grown up in New York City, she uses the symbol of a housecoat to explore minimalism, beauty, matriarchy, and family. As someone who also grew up in New York, I remember many a grandmother in these ubiquitous housecoats and appreciate how this simple garment personifies so many memories and stories. This choice, mixed with vibrant tropical colors and flowers, also honors her grandmother (who was a seamstress) and the routes Perez’s grandparents and parents took from Puerto Rico to America. While the silhouettes in her paintings outline the garment, the lines create a different kind of topography that reminds me of maps and the outline of islands. With immigrant roots and routes in my own family, I appreciate this thread.

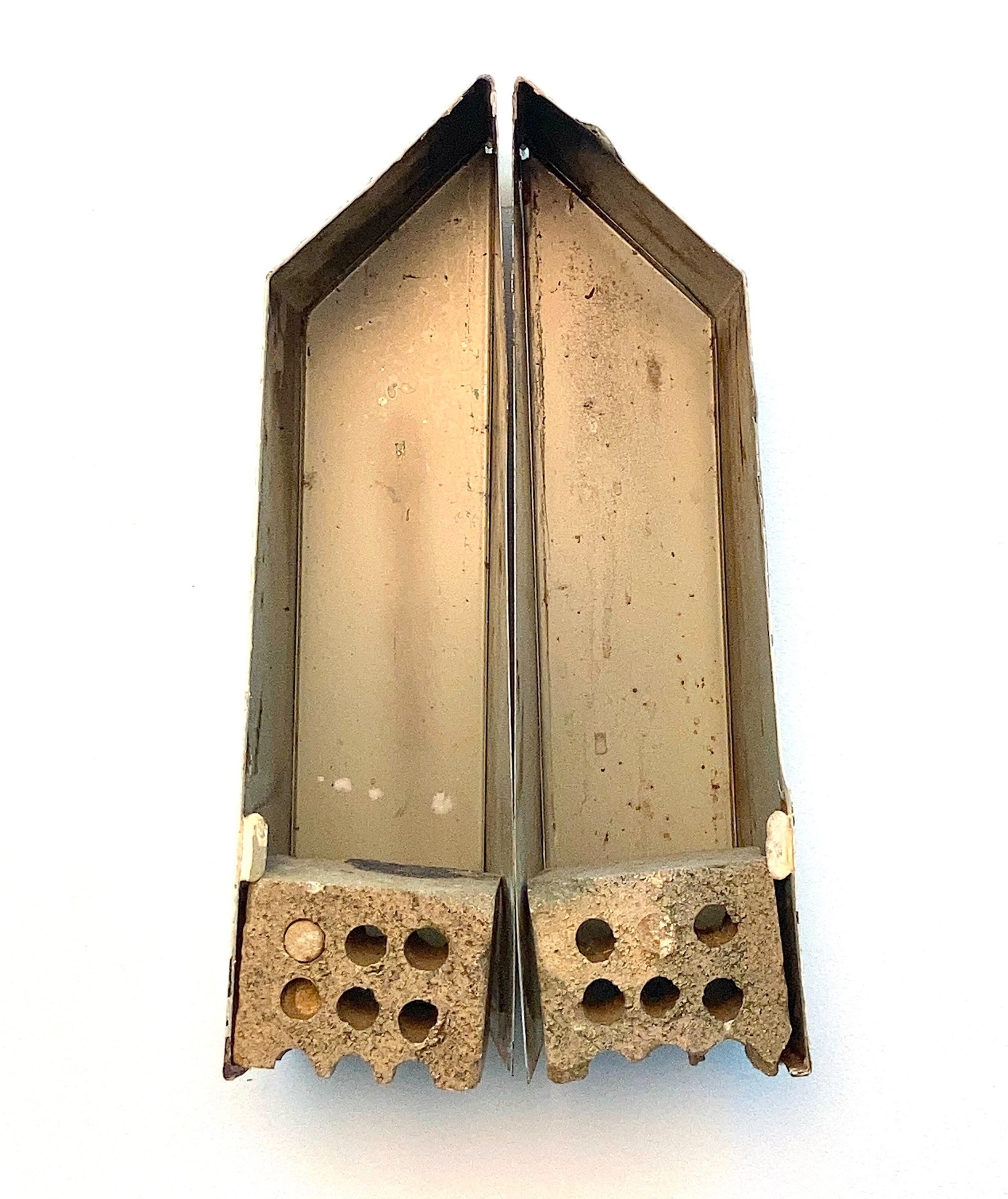

Kanchan Balsé uses found objects to examine the roots of the materials themselves. She invites viewers to consider the emotional resonance and history of these objects while raising questions about why artists choose particular materials and what should be considered archival. There is an archeological element to her work that challenges us to reflect on how we repair, raze, discard, or start over. Like Friedman, she sees significance and elegance in discarded items regularly ignored. There is an accessibility to her work that reminds me of beauty in the everyday-ness of life. She also helps us all to remember that it is hard to grow deep roots of any kind if we are in a constant cycle of disposability.

Louisa Neill and Maggie Gourlay similarly reflect on the environmental impact of their work. From clay to paper to pigments, both source their own materials and look for ways to keep art’s ethical implications in sharp focus.

Neill thinks deeply about big-picture concepts. She is driven by the function objects have in our daily lives, as well as how people relate to each other and their environment. Like Balsé, she thinks about disposability, but she also considers the actual routes traveled throughout the manufacturing and transportation process. Her work embodies the tangle of those operations and foregrounds her love of geometry, structure, and problem-solving. Her three-dimensional work is also a nod to her present studies in architecture and the built environment.

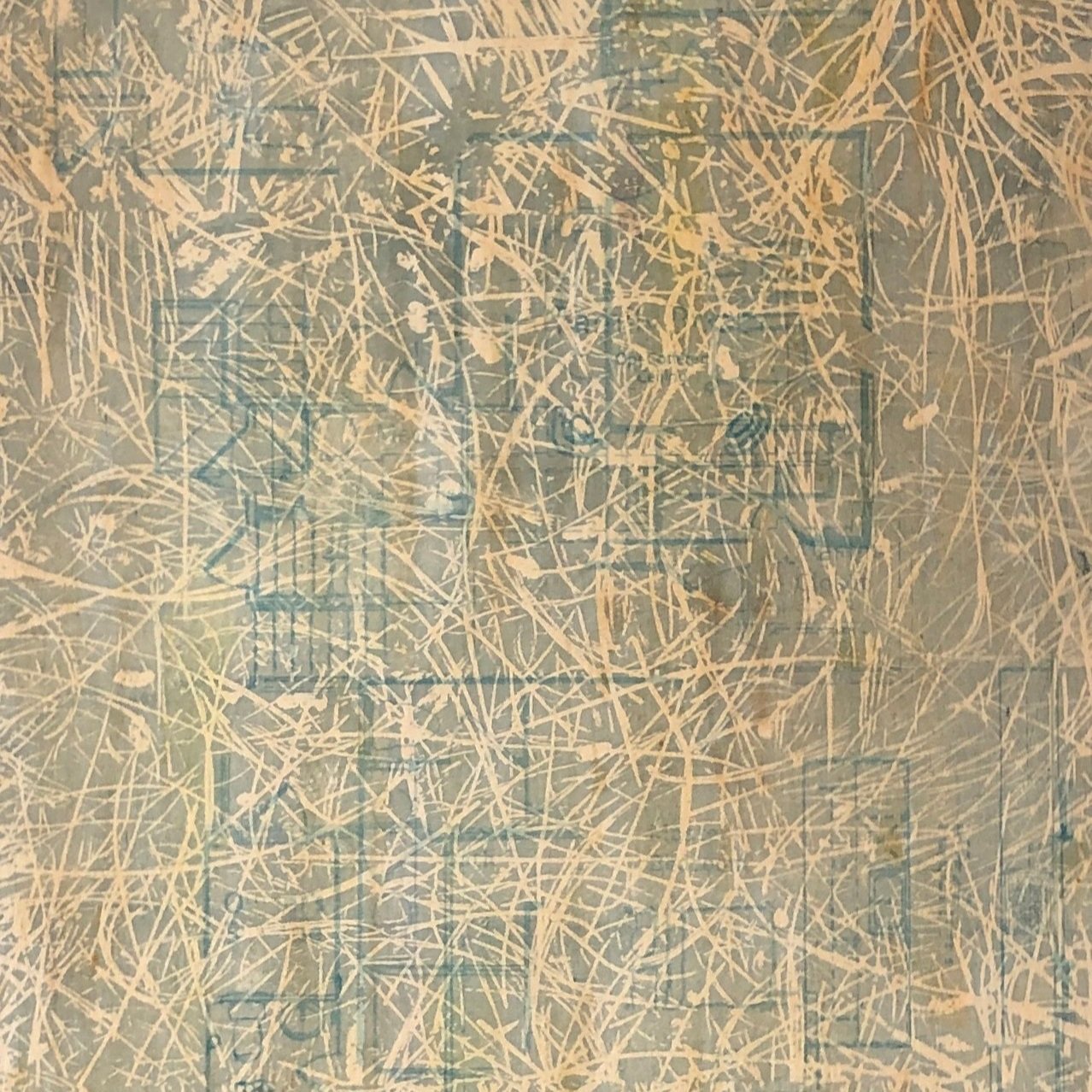

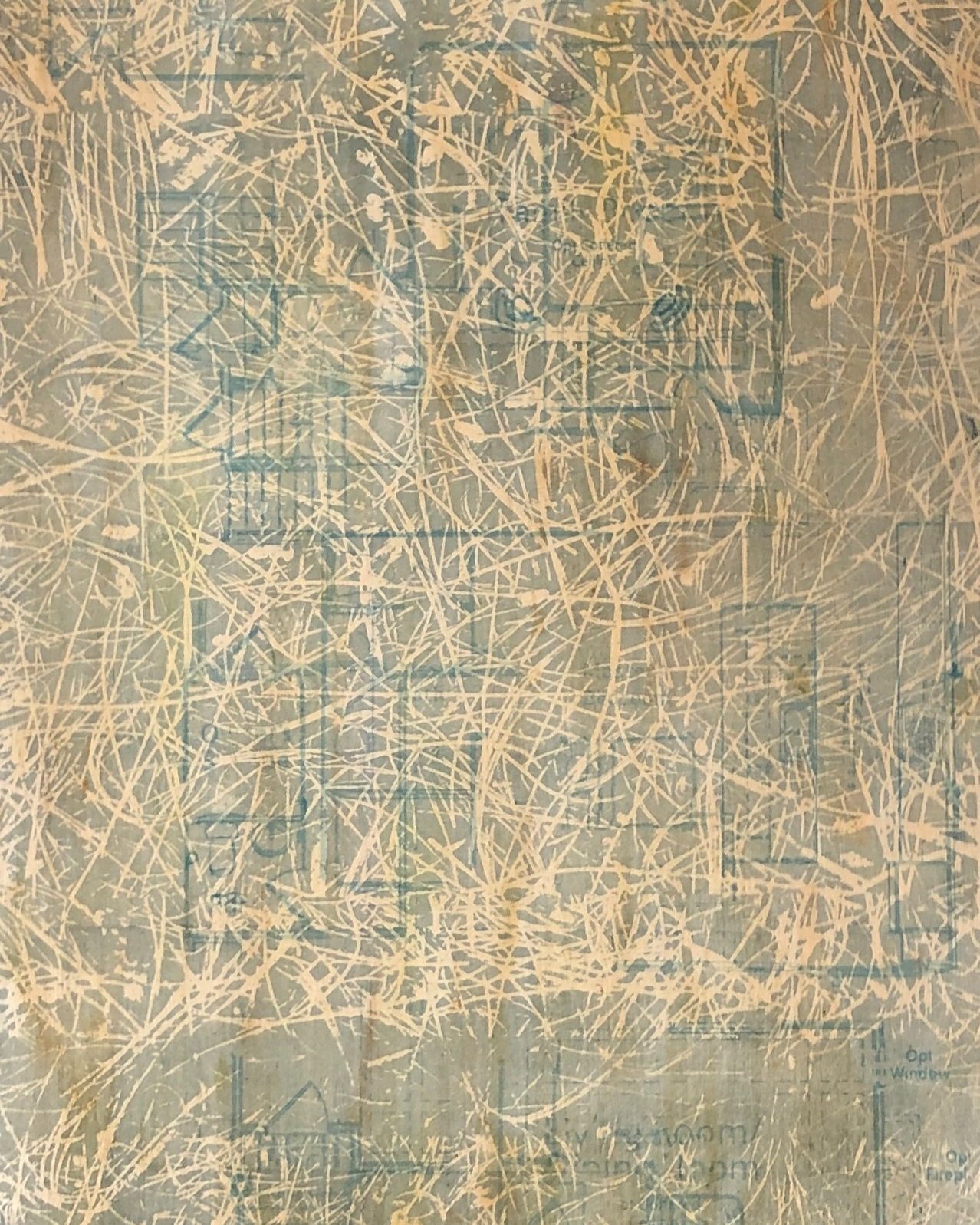

Gourlay’s pieces are grounded in the natural environment. By wanting to “green her studio,” she uses plant-based pigments and dyes to screenprint on natural fabrics as a way to honor nature. She introduced me to the idea of soymilk as a base for pigment and how it must be used within a week. This fragility points to her critique of the pesticide industry and how it depletes and poisons the soil. The dandelions pictured on her fabric piece are considered weeds by many US gardeners, yet the leaves are served in many US kitchens and are vital to the ecosystem. Therefore, by screenprinting dandelions all over, she shines a light on the debate about invasive versus native species. This environmental veneration is also echoed in the ghostly shadows of pine cones and needles, barely masking the blueprint laid on top. It looks like a shadow beneath the forest, but it signals what is to come—the roots and routes of our so-called “progress.” In a city like DC, where gentrification and construction loom over almost every corner, the roots of profits seem to perpetually threaten the roots of the people.

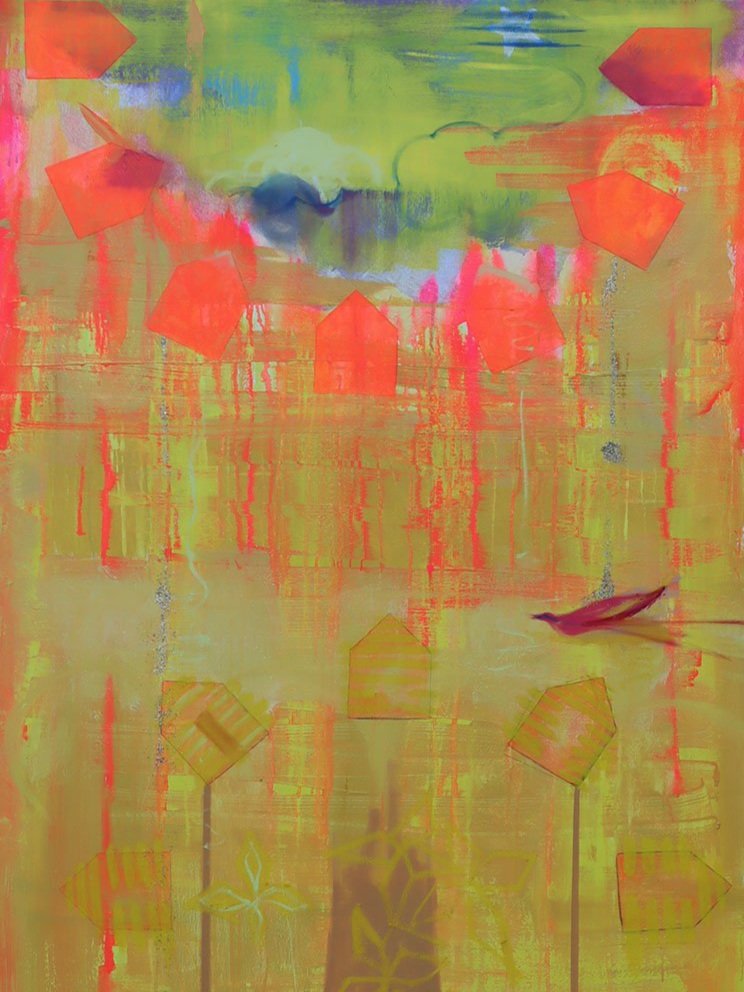

With a degree in urban planning, Pixie Alexander constantly thinks about structures and how systems can disempower people, particularly women. Another Alabama native via Mobile, she has a background in photography, dance, painting, sculpture, and digital work. With such a range of artistic expressions, she likes to “let the idea come first and let the form follow.” In this exhibition, Alexander’s painting takes center stage with chromatic studies of house forms and the routes between them. However, I am reminded that houses are also such potent representations of rootedness and who does or does not have access to the vital resource of housing. There is also, for better or for worse, so much hidden inside of homes. From celebrations to tragedies, “home” can be simultaneously stabilizing and destabilizing, the roots of dynamism and dysfunction, and Alexander’s bold palette conjures a range of possibilities for the communities she creates on canvas.

Caroline MacKinnon also thinks deeply about nature and community. Inspired by natural wonders such as Niagara Falls, her work invites audiences to think about their connections to the Earth and to one another. In a recent project, MacKinnon invited audiences to create small textured objects from clay, which she later glazed and fired. She then wired all of the finished pieces together into a larger structure to embody some of the ties between people. It also demonstrated the power of community participation, which is present in a lot of her work. In the paintings exhibited here, she uses saturated colors, embroidery, beads, and ceramic elements to evoke the expansiveness of the cosmos.

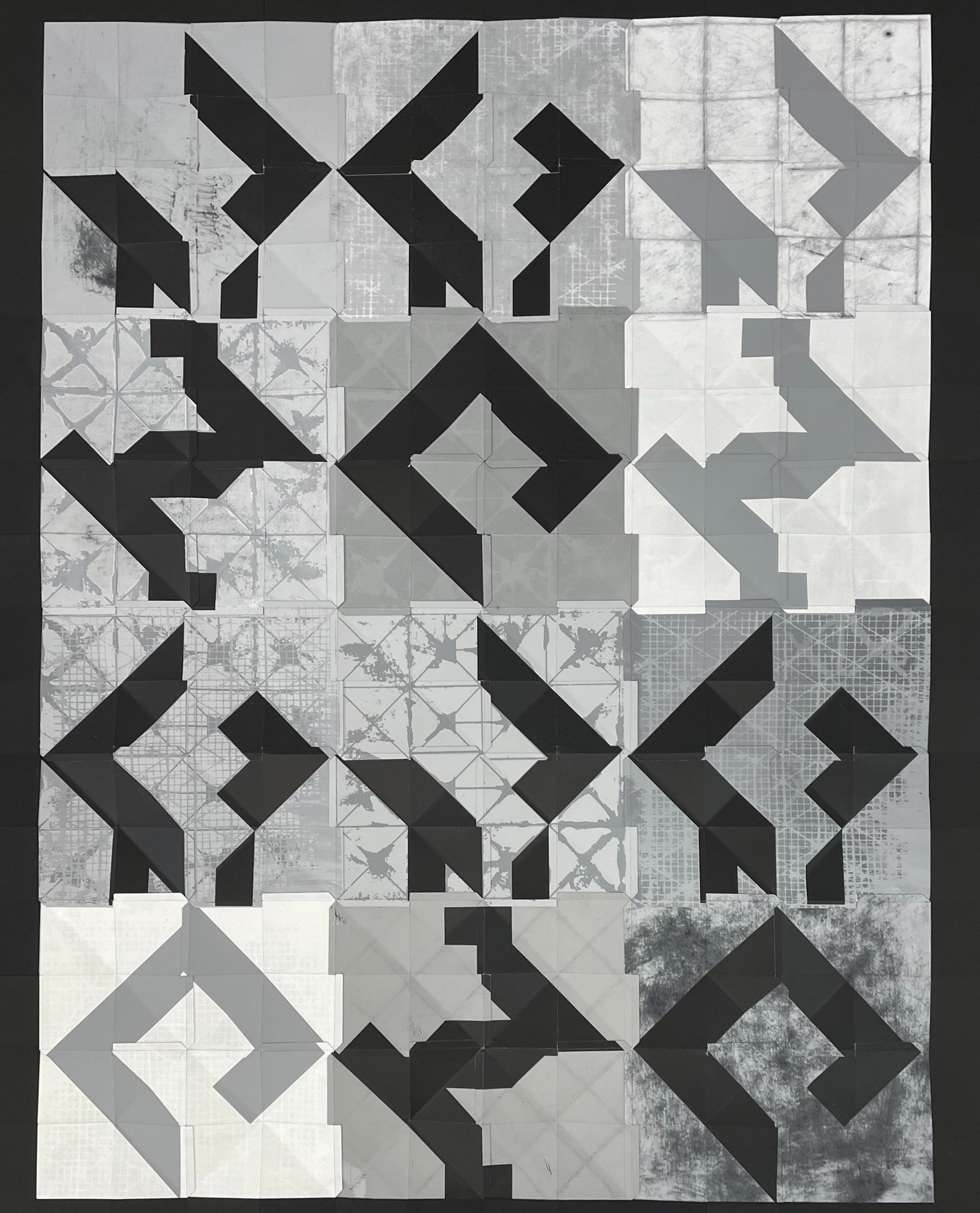

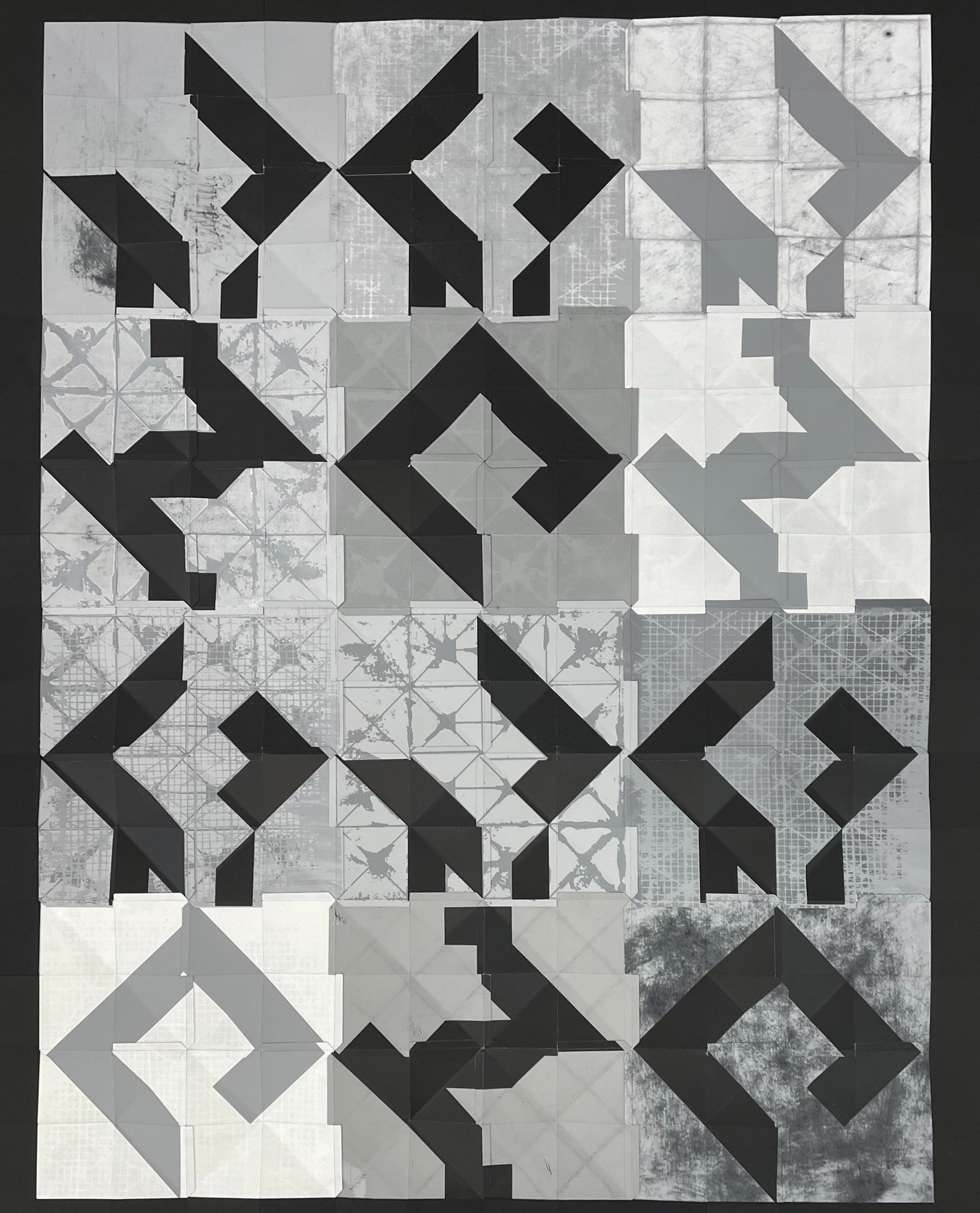

Adi Segal also folds stories into her work through the literal creases she makes in paper. Recalling the folding games that her grandfather played with her as a child, she described how he used to paint the various hidden squares in such a way that every time she opened a different flap, it prompted him to narrate a different part of a larger story; like a choose-your-own-adventure book, she could move the flaps to reveal the tale in different ways each time. While I played various folded paper games as a child, they were mostly dedicated to the supposed fortune-telling of my friends’ lives; there was nothing remotely close to the richness of this experience, and I was captivated by the possibility of replicating the practice in a community workshop about storytelling and identity. Segal thinks a lot about identity and its imperfect lines. As the first generation of her family living in the US, she has parents from two cultures and interrogates her own American-ness. Yet, with a family touched by adoption, she also contemplates how she will connect her children to their ancestral roots. In this piece, she creates her own geometric language, like how she and her children are making new traditions. Although the repetition of the shapes is sometimes imperfect, for me, the consistent patterns across the quilted paper point to the power of her grandfather, still anchoring her family together.

Shelley Picot invokes the legacy of children as well. However, she channels her autobiographical experiences to focus on adolescent girls by using roots as beginnings and routes as transformations. Situated in a mythical bathroom, her whimsical sink and mirror represent the site of these pivotal pubescent changes. The collaged images above the mirror are similar to a wall of pictures in a teenager’s room or the inside of a school locker—pictures that both inform and influence how they see themselves. For some young people, these images are the root of great insecurity, while for others, they are the source of great strength. Either way, the tiny mirror underneath these collaged images leads me to believe that a small reflection of one’s true self—the root of who you really are—ultimately remains.

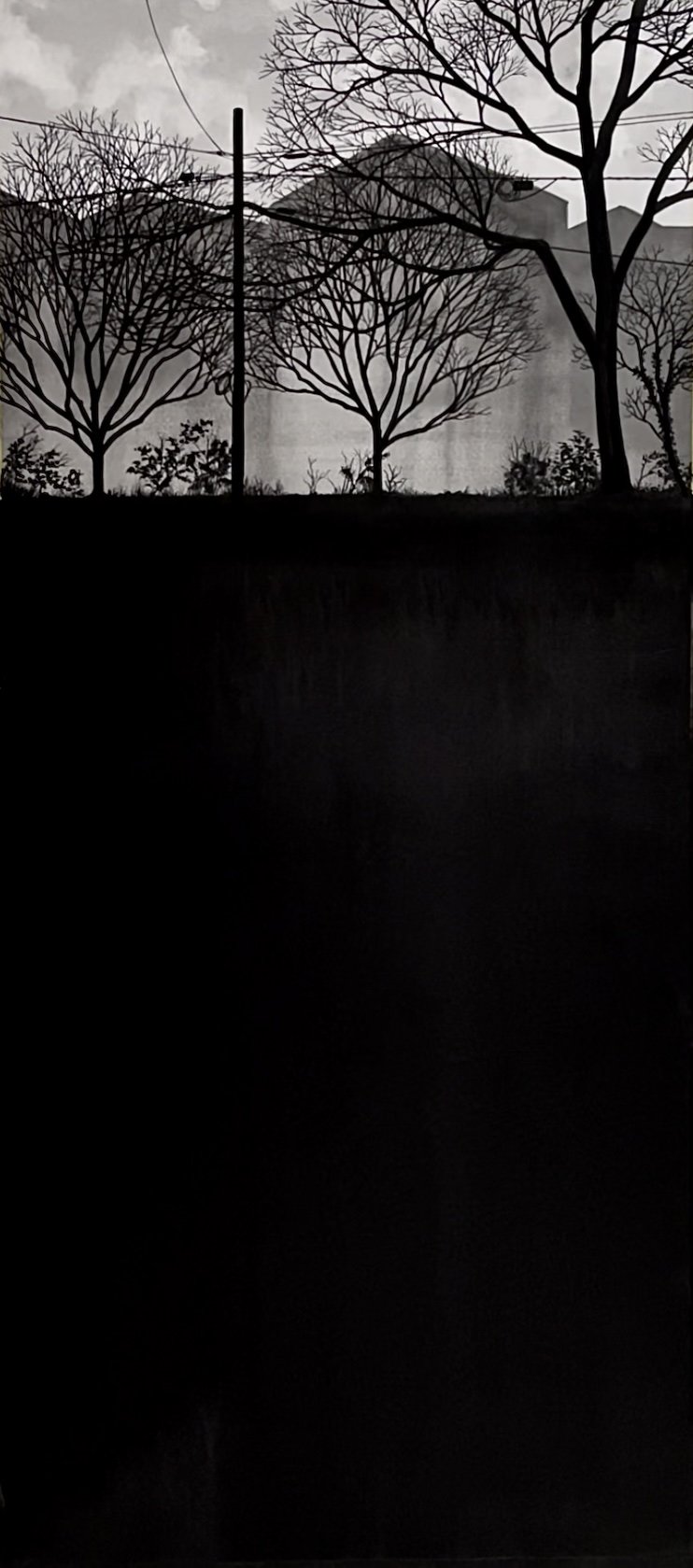

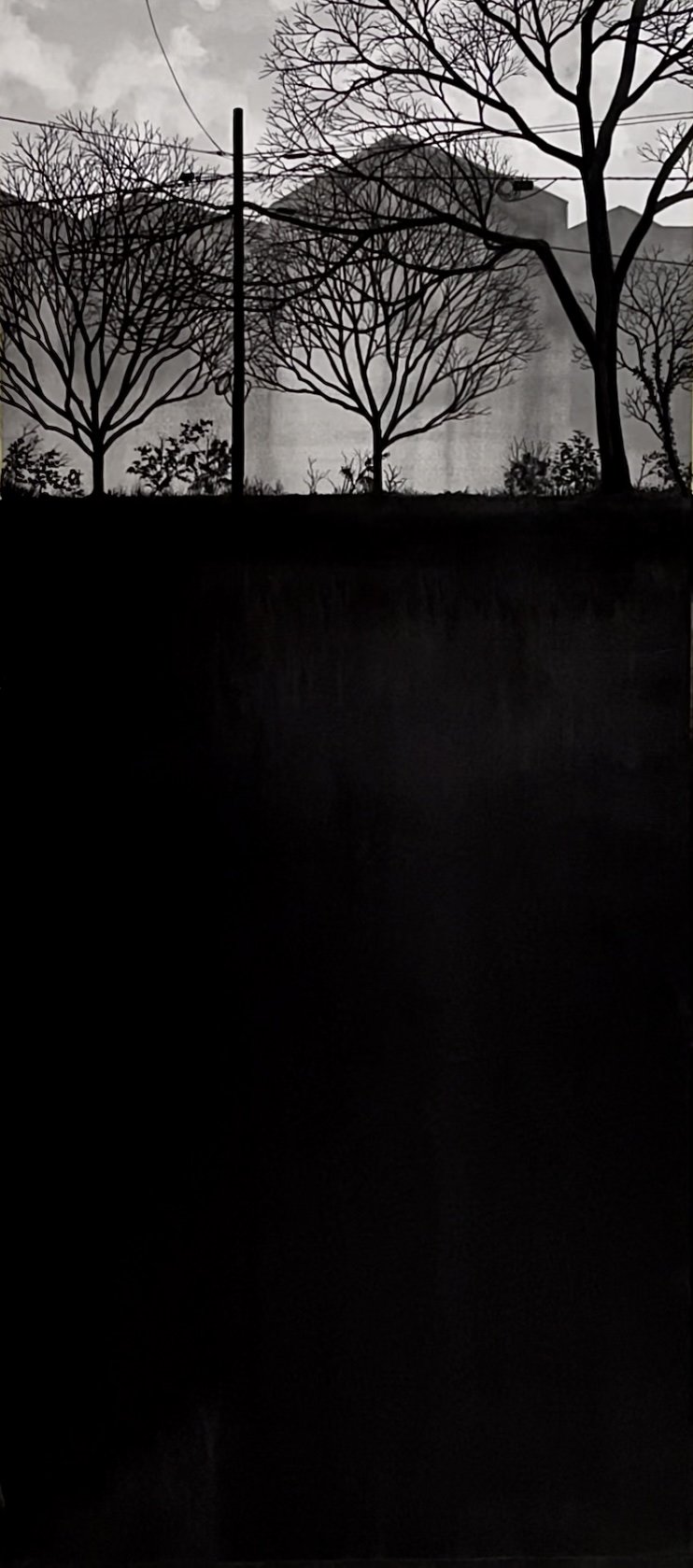

Alex L. Porter’s work rounds out the exhibition with landscape portraits of trees and power lines—the roots of the natural world entangled with the routes from the human-made world. He uses calligraphy ink on heavy-duty watercolor paper to render DC cityscapes in sharp silhouettes. By zooming in on specific points where the trees and poles intersect, we are confronted with a swirl of similarities—tree limbs look like electric wires and tree trunks look like utility poles. The natural and human-made worlds are enmeshed in ways that those who live in large cities have grown accustomed to. Conventional landscape painting depicts mountains, valleys, forests, fields, and bodies of water. They may or may not include human-made structures. However, those tend to be people or small buildings. I do not generally associate utility poles with landscape paintings. Porter flips the techniques of representational landscape painting to capture the scenic views that surround him; this is the landscape that is actually here. He is not stealing away to give us a bucolic countryside. Instead, he reflects the city’s real growth (for better or worse) in stark black and white.

Overall, this collective gives us many rich ways to think about the theme of roots and routes. To bring hope to our future we need to be firmly grounded and purposefully visioned—rooted and routed. However, hope is more than just optimism. I like how the folks from the Equinox Counseling & Wellness Center in Colorado put it:

Hope is a sense that things can be made better through action, while optimism is a more ephemeral belief that everything will be OK…. Optimism is a positive thought pattern. Hope involves setting goals and following through on them. …hope is a more potent force and better for our health and well-being…. [because] Hope makes people act.

Knowing our roots and routes can help us take principled action. If nothing else, it can certainly be the catalyst for healing conversations in our personal and professional lives. Therefore, let us remember the saying, “Where attention goes, energy flows.” Let these artists help to focus our attention on key considerations to make brighter tomorrows in our communities and beyond.

— Gia Harewood

FROM THE CURATOR

FROM THE CURATOR

The beginning of a new calendar year tends to be filled with celebration and reflection, hopeful resolutions, and deep introspection. January itself often feels packed with a recharged promise of renewal, new chances to potentially do things differently, and overall commitments to be better. Yet, just four months into 2024, there are still multiple wars with increasing death tolls, continued climate destruction, punitive policies targeting marginalized identities, and intensifying political divisions. As the presidential election creeps closer and closer in the United States, sociopolitical hostilities feel like they are stifling connection, collaboration, and calm. It is easy to look at the news and lose hope.

However, Bryan Stevenson, lawyer and founder of the Equal Justice Initiative, reminds us that hope is vital. In his commencement speech to Ohio State University’s 2023 graduates, he says, “Our hope is key. Our hope is our superpower…hopelessness is the enemy of justice.” Stevenson connects hope to the political and the personal; he sees a just society as inextricably linked to it. In many ways, I am also calling for hope. To develop the superpower that Stevenson describes, the steadfast hope needed to weather any turbulent political or personal storms, I believe we need to be grounded and firmly rooted; we each need to understand the histories of who we are, where we have come from, and where we are going so as to gather strength from these knowings — essentially the roots and routes of both self and society.

Because The DC Arts Center’s (DCAC) mission is to foster underrepresented artists, Sparkplug as a signature initiative amplifies the organization’s roots. DCAC was founded as a platform for those who have been gatekept out of more traditional gallery spaces, thereby enabling a more diverse pool of artists (and curators) to reach wider audiences. Having been a 2014 Curatorial Initiative awardee, I am grateful for how their presence jumpstarted my curatorial career, and I am honored to be back in this full-circle then-and-now moment.

This exhibition also celebrates the various artistic routes that these creatives have traveled throughout the program and will continue to take in the future. However, as Toni Morrison states in her 1987 novel Beloved, “Definitions belong to the definers, not the defined.” To that end, these ten artists—Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal—explore the exhibition’s theme in unique ways, sharing what is most relevant to them and resonant with their practice. I am energized by their visions of what art can do and am hopeful that their talents will inspire audiences to find common ground and face the difficult dialogues and decisions in our sociopolitical futures.

Several artists use found objects to plumb the depths of family histories. Gayle Friedman has a reverence for things that people no longer find useful and bandsaw blades give her the perfect material manifestation for how we walk in the world. She describes it as a combination of “tension and danger.” However, I was even more fascinated with how the blades provide a powerful metaphor and entry point into racial dialogues. She is a white Jewish woman from an all-white suburb just outside of Birmingham, Alabama who was unaware of the racialized violence happening just a few miles away until she moved out for college. Therefore, I see the tension and danger in the toll that racism takes on everyone—sometimes it is exposed and raw (like the unpainted blades), sometimes it is covered up and packaged (like the painted blades), but either way, it can never be contained—it will always break through the surface (like the blade jutting over the panel board’s frame).

Rebecca Perez also digs into her family’s Puerto Rican roots through material objects. Having grown up in New York City, she uses the symbol of a housecoat to explore minimalism, beauty, matriarchy, and family. As someone who also grew up in New York, I remember many a grandmother in these ubiquitous housecoats and appreciate how this simple garment personifies so many memories and stories. This choice, mixed with vibrant tropical colors and flowers, also honors her grandmother (who was a seamstress) and the routes Perez’s grandparents and parents took from Puerto Rico to America. While the silhouettes in her paintings outline the garment, the lines create a different kind of topography that reminds me of maps and the outline of islands. With immigrant roots and routes in my own family, I appreciate this thread.

Kanchan Balsé uses found objects to examine the roots of the materials themselves. She invites viewers to consider the emotional resonance and history of these objects while raising questions about why artists choose particular materials and what should be considered archival. There is an archeological element to her work that challenges us to reflect on how we repair, raze, discard, or start over. Like Friedman, she sees significance and elegance in discarded items regularly ignored. There is an accessibility to her work that reminds me of beauty in the everyday-ness of life. She also helps us all to remember that it is hard to grow deep roots of any kind if we are in a constant cycle of disposability.

Louisa Neill and Maggie Gourlay similarly reflect on the environmental impact of their work. From clay to paper to pigments, both source their own materials and look for ways to keep art’s ethical implications in sharp focus.

Neill thinks deeply about big-picture concepts. She is driven by the function objects have in our daily lives, as well as how people relate to each other and their environment. Like Balsé, she thinks about disposability, but she also considers the actual routes traveled throughout the manufacturing and transportation process. Her work embodies the tangle of those operations and foregrounds her love of geometry, structure, and problem-solving. Her three-dimensional work is also a nod to her present studies in architecture and the built environment.

Gourlay’s pieces are grounded in the natural environment. By wanting to “green her studio,” she uses plant-based pigments and dyes to screenprint on natural fabrics as a way to honor nature. She introduced me to the idea of soymilk as a base for pigment and how it must be used within a week. This fragility points to her critique of the pesticide industry and how it depletes and poisons the soil. The dandelions pictured on her fabric piece are considered weeds by many US gardeners, yet the leaves are served in many US kitchens and are vital to the ecosystem. Therefore, by screenprinting dandelions all over, she shines a light on the debate about invasive versus native species. This environmental veneration is also echoed in the ghostly shadows of pine cones and needles, barely masking the blueprint laid on top. It looks like a shadow beneath the forest, but it signals what is to come—the roots and routes of our so-called “progress.” In a city like DC, where gentrification and construction loom over almost every corner, the roots of profits seem to perpetually threaten the roots of the people.

With a degree in urban planning, Pixie Alexander constantly thinks about structures and how systems can disempower people, particularly women. Another Alabama native via Mobile, she has a background in photography, dance, painting, sculpture, and digital work. With such a range of artistic expressions, she likes to “let the idea come first and let the form follow.” In this exhibition, Alexander’s painting takes center stage with chromatic studies of house forms and the routes between them. However, I am reminded that houses are also such potent representations of rootedness and who does or does not have access to the vital resource of housing. There is also, for better or for worse, so much hidden inside of homes. From celebrations to tragedies, “home” can be simultaneously stabilizing and destabilizing, the roots of dynamism and dysfunction, and Alexander’s bold palette conjures a range of possibilities for the communities she creates on canvas.

Caroline MacKinnon also thinks deeply about nature and community. Inspired by natural wonders such as Niagara Falls, her work invites audiences to think about their connections to the Earth and to one another. In a recent project, MacKinnon invited audiences to create small textured objects from clay, which she later glazed and fired. She then wired all of the finished pieces together into a larger structure to embody some of the ties between people. It also demonstrated the power of community participation, which is present in a lot of her work. In the paintings exhibited here, she uses saturated colors, embroidery, beads, and ceramic elements to evoke the expansiveness of the cosmos.

Adi Segal also folds stories into her work through the literal creases she makes in paper. Recalling the folding games that her grandfather played with her as a child, she described how he used to paint the various hidden squares in such a way that every time she opened a different flap, it prompted him to narrate a different part of a larger story; like a choose-your-own-adventure book, she could move the flaps to reveal the tale in different ways each time. While I played various folded paper games as a child, they were mostly dedicated to the supposed fortune-telling of my friends’ lives; there was nothing remotely close to the richness of this experience, and I was captivated by the possibility of replicating the practice in a community workshop about storytelling and identity. Segal thinks a lot about identity and its imperfect lines. As the first generation of her family living in the US, she has parents from two cultures and interrogates her own American-ness. Yet, with a family touched by adoption, she also contemplates how she will connect her children to their ancestral roots. In this piece, she creates her own geometric language, like how she and her children are making new traditions. Although the repetition of the shapes is sometimes imperfect, for me, the consistent patterns across the quilted paper point to the power of her grandfather, still anchoring her family together.

Shelley Picot invokes the legacy of children as well. However, she channels her autobiographical experiences to focus on adolescent girls by using roots as beginnings and routes as transformations. Situated in a mythical bathroom, her whimsical sink and mirror represent the site of these pivotal pubescent changes. The collaged images above the mirror are similar to a wall of pictures in a teenager’s room or the inside of a school locker—pictures that both inform and influence how they see themselves. For some young people, these images are the root of great insecurity, while for others, they are the source of great strength. Either way, the tiny mirror underneath these collaged images leads me to believe that a small reflection of one’s true self—the root of who you really are—ultimately remains.

Alex L. Porter’s work rounds out the exhibition with landscape portraits of trees and power lines—the roots of the natural world entangled with the routes from the human-made world. He uses calligraphy ink on heavy-duty watercolor paper to render DC cityscapes in sharp silhouettes. By zooming in on specific points where the trees and poles intersect, we are confronted with a swirl of similarities—tree limbs look like electric wires and tree trunks look like utility poles. The natural and human-made worlds are enmeshed in ways that those who live in large cities have grown accustomed to. Conventional landscape painting depicts mountains, valleys, forests, fields, and bodies of water. They may or may not include human-made structures. However, those tend to be people or small buildings. I do not generally associate utility poles with landscape paintings. Porter flips the techniques of representational landscape painting to capture the scenic views that surround him; this is the landscape that is actually here. He is not stealing away to give us a bucolic countryside. Instead, he reflects the city’s real growth (for better or worse) in stark black and white.

Overall, this collective gives us many rich ways to think about the theme of roots and routes. To bring hope to our future we need to be firmly grounded and purposefully visioned—rooted and routed. However, hope is more than just optimism. I like how the folks from the Equinox Counseling & Wellness Center in Colorado put it:

Hope is a sense that things can be made better through action, while optimism is a more ephemeral belief that everything will be OK…. Optimism is a positive thought pattern. Hope involves setting goals and following through on them. …hope is a more potent force and better for our health and well-being…. [because] Hope makes people act.

Knowing our roots and routes can help us take principled action. If nothing else, it can certainly be the catalyst for healing conversations in our personal and professional lives. Therefore, let us remember the saying, “Where attention goes, energy flows.” Let these artists help to focus our attention on key considerations to make brighter tomorrows in our communities and beyond.

— Gia Harewood

![Gayle Friedman - Cotton Candy Swirl, 2023 [MIGHT NOT USE].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/61fad3cbcd8eca2fcf42b62f/80ba6616-9bc2-48cd-98b3-6d41d0290a72/Gayle+Friedman+-+Cotton+Candy+Swirl%2C+2023+%5BMIGHT+NOT+USE%5D.jpeg)

![Gayle Friedman - Cotton Candy Swirl, 2023 [MIGHT NOT USE].jpeg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/61fad3cbcd8eca2fcf42b62f/d7511e4b-706d-4095-9c7e-4191b358eab9/Gayle+Friedman+-+Cotton+Candy+Swirl%2C+2023+%5BMIGHT+NOT+USE%5D.jpeg)

Meet the Curator & Artists

Gia Harewood, Pixie Alexander, Kanchan Balsé, Gayle Friedman, Maggie Gourlay, Caroline MacKinnon, Louisa Neill, Rebecca Perez, Shelley Picot, Alex L. Porter, and Adi Segal

ABOUT THE CURATOR: Gia Harewood

Gia Harewood is an educator, curator, and facilitator. Having graduate degrees in English from the University of Maryland College Park, she believes in the power of storytelling to connect, heal, and transform.

Through the lens of her graduate degree in Applied Theatre from The City University of New York (CUNY)’s School of Professional Studies, Gia uses the arts (broadly defined) to amplify and catalyze group dialogue and social justice work.

When she’s not listening to multiple audiobooks and podcasts at a time, you can find her soaking up memorable performances on stage and screen, riveted by insightful exhibitions and NPR segments, dancing, roller skating, and looking for yet another book.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Pixie Alexander

I sat with Gia Harewood, our curator, in conversation last spring and was prompted with the notion of “Roots, Routes.”

For years, I had been working with large, gridded paintings that flirted (at times) with elements of language and figuration. Lately, the paintings have been infused with repeating house forms, suggesting housing developments, and emerging as a relic of my time studying urban planning: I hold an MS from Columbia University with a focus on housing. After my conversation with Gia these paintings left the realm of the grid and became houses in circular patterns. When, around this same time, I found out that a childhood friend had passed away suddenly of a brain aneurysm, I felt myself reaching into memory more, and the intimacy of friendship, play, invention, and freedom that I had felt with her as we ran wild through our neighborhood: a circle of small houses in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Within the general structure of a circle of house forms in an oversized rectangle, an ontology of mark-making became a meditation. It became suffused with the memory I had invited into the studio through a life-sized drawing of my childhood friend as she stood in our long-ago yard with her bicycle, waiting to embark on another adventure, as we did. Roots, Routes.

The “roots” are Alabama, childhood, and home, however fractured. The “routes” are the infrastructures we inhabit, the roads to adventure.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Kanchan Balsé

My process starts outside, looking for objects of all kinds for my compositions. They come from many places, including those that challenge me to consider ideas of belonging and property, such as secluded spots at night or areas marked with no trespassing signs.

Scavenging along train tracks, climbing fences, and hauling concrete from beneath bushes is physically demanding and exciting and has elements of archeology, defiance, and reclamation. I’m drawn to places where the built and natural environments are tangled. I retrieve things that elicit visceral emotional responses (an open envelope growing mold, a dirty glove, a discarded mop head) and collect them for further exploration and connection with other materials in the studio. The work is creating my own language with which to understand self, place, and agency.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Gayle Friedman

Roots & Routes has me traveling back—back to the whirlwind of a Birmingham childhood in the 1960s, to a mash-up of joy and tension, anxiety and play. I had no idea what was going on. And now maybe I do…a little bit.

In my work I search for hidden messages and meaning within found and inherited objects. I’m currently focusing on bandsaw blades. I place them in unexpected contexts to reveal and subvert their traditional uses. The blades cast shadows and interact with their surroundings to become gestural line drawings.

In my experience, anxiety has been a frequent companion, conniving to undermine life’s joy and spontaneity. I try hard to maintain control, imagining I can thwart potential dangers. The bandsaw blades are inherently tense, have sharp teeth, and make the perceived danger real. I submit to the possibility that my work will spring apart, jump off the wall, and cause real harm. I don’t use glue so as to create the impression that the unexpected could occur. This work addresses my desire to live fully and with joy in an uncertain world. Each piece is an exercise in maintaining and releasing control.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Maggie Gourlay

The work exhibited here is based on my observations of ecological changes occurring in my neighborhood. In the context of species extinction, we forget what we have lost so that the present is the new baseline. To cope with this loss, I endeavor to observe, remember, and record the natural world around me, focusing on botanical species. The fiber work in this show, Grounding, is a tribute to the resilient and unsung heroes—the weeds and wildflowers, such as the common dandelion--that help regenerate our depleted soils. The work, History Lessons, is an homage to a grouping of pine trees I once walked among, now sacrificed to build a home. As tributes and expressions of loss, they hold space against disappearance.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Caroline MacKinnon

My artwork is inspired by the natural world, evoking the shapes of its flora, fauna, and their environs without directly copying specific species or existing places.

In my gouache and mixed-media paintings, as well as my hand-built ceramic sculptures, I use saturated colors and tiny patterns to create glowing, moody vistas. These fantastic places and odd objects are from the past, the present, or the future. They are both elemental and ephemeral.

I often start with the seed of an idea. “A skyscape full of stars.” “A creek bed with hundreds of colorful rocks.” Then, I get to work, with the rest of the elements falling into place during the process of creation. Sometimes, the seed sprouts suddenly, as if from a dream. Sometimes, it germinates after I gather stones or pinecones on an outdoor walk.

I feel compelled to explore our relationships with the Earth and one another, always searching to understand our place in the cosmos.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Louisa Neill

From where do the materials and objects that surround us originate? And where do they go once they pass through our lives? Within our global economy, object production and object life cycles are often complex and multifaceted. My drawings, From there to here, from here to there, and From there to where, emerged from my consideration of these questions and the difficulty I faced in finding complete answers. I wonder about the routes natural resources and human-made materials take and how these systems hold up when viewed through an ethical lens and efficiency focus. Relatedly, I wonder how these routes relate to my own (and our societal) consumerist and economic conditions/choices.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Rebecca Perez

My latest work explores loss and longing through the lens of the common house dress, or “bata,” in Spanish. Batas are traditionally worn by Latina mothers and grandmothers while carrying out their housekeeping and caretaking tasks. My grandmothers and great-grandmothers wore them all the time. This common but powerful garment is a symbol of home–maternal and matriarchal connections. These paintings combine pattern and flower imagery with brushwork and circular lines to depict their multilayered influence on my life, as well as a longing for home and a question about how my place in the world looks so different from theirs.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Shelley Picot

The inhuman beings in my work reflect our most human qualities in isolation. Cartoonish dogs, aliens, and ghosts are among a growing set of characters that tell stories about protection and vulnerability, regret and mourning, and everything we worry about before we fall asleep.

With a style influenced by comics, I work serially across sculptures, drawings, and videos. I pay particular attention to the ways that different dimensions intersect: paper clay acts as both a sculptural material and a surface for drawing, while constructed masks and props become elements for videos and projections.

In my current project, I use the story of a termite queen molting as a parallel for the complex mix of freedom and loss in the transformation from girlhood to adulthood.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Alex L. Porter

Building on one of the longest-standing traditions of image-making –applying ink, by hand, to paper–I try to distill the aesthetic and visceral experience of a boundless sprawl into vivid graphics. These landscapes are essentialized as chaotic growth, often altered by human or other interventions. Everything in them, whether constructed or sprung from the earth, joins the tangle of disparate elements that make up the natural world. Through the carefully detailed rendering of limbs and branches, my art seeks to capture the spectacular pantomime of this process. Greater emphasis is placed on the gesture of these landscape elements than the scenes they eventually compose. They resist the pastoral landscape, which draws the viewer in, and instead present these elements as stark icons that hold them at a distance.

ABOUT THE ARTIST: Adi Segal

I am a visual artist working at the intersection of art and community. My work centers around cultural identity and the perception of identity. I use experimental screenprinting, paper folding, and mixed media to visualize abstract questions.

I am currently exploring generational identity. My family, like many today, is scattered across space, race, religion, and culture. I am a first-generation American and a mother of two, including an adopted son. Where am I really from? What connects my children to their ancestors (biological and adopted)?

I investigate these questions grounded in my grandfather’s paper-folding games. Combining their sequencing patterns with the language of Gee’s Bend quilts, color theory, and personal history, I am actively connecting my family’s layered identities.